- Home

- Alan Scholefield

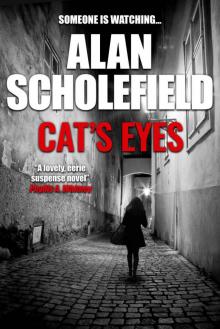

Cat's Eyes

Cat's Eyes Read online

Cat’s Eyes

Alan Scholefield

© Alan Scholefield 1981

Alan Scholefield has asserted his rights under the Copyright, Design and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work.

First published in 1981 by Hodder and Stoughton Limited.

This edition published in 2017 by Endeavour Press Ltd.

Table of Contents

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

1

First the tapping.

It came above the noise of the wind and the rain. A tapping. At the window.

Then the man’s face.

Rain pouring down his heady mixing with the blood; dark holes where his eyes should have been; white fingers pressed against the glass.

Sometimes it was Bill’s face; sometimes Charlie’s.

Then came the scream. She seemed to stand outside herself and watch herself screaming.

Always the tapping. Tap ... tap ...

Then the face. Then the scream.

Then the cat.

It sat in the middle of the shining black road: huge, lit from behind like some giant monolith.

Then the crash ...

2

Rachel Chater could feel the scream in her throat as she swam up through the layers of sleep and broke into wakefulness. Her mouth was open but no sound came; the scream had been silent, like her sleep. She opened her eyes and reached for Bill, but he was not there.

For a second, she felt panic, then she remembered: Bill was on his way to California and she was here, in the house tucked into the Sussex Downs, with her baby daughter, Sophie, the girl Penny and Nurse Griffin for company.

Her knee was aching and the dream was still vivid in her mind, its elements separating into stages, each stage remorselessly following the last, gathering speed as it had in reality, until the final black-out.

She told herself that now it was only a dream, and fought the tension in her body. She remembered the yoga exercise for relaxing: place the thumbs against the first fingers to make a circle and let them rest by your sides; allow yourself to relax, concentrate on each muscle, let the muscles become jelly. Slowly, she felt her body soften. The throb in her right knee became worse but the dream began to disappear as though down the small end of a telescope, until finally it was gone, and only the desolation and loneliness remained. The day stretched ahead of her and she began to wonder how on earth she would fill it — and all the other days — until Bill came home.

Home? Hell, this wasn’t home! She pushed back the blankets and dragged herself painfully from the bed. Her injured knee had stiffened and she put her weight on it gingerly. It had let her down several times when she had tested it in hospital and she had ended up in a heap on the floor. But the doctors had said she must walk, so each time she had hauled herself up, grimly, and tried again. Now she hobbled to the window and drew back the curtains.

It was early autumn, a damp, grey morning, and she looked out over the dripping landscape which was uninterrupted by any other sign of human habitation.

Suddenly she yearned for the sea, real sea, the Pacific off Santa Monica; the great swells coming into the Monterey Peninsula; even the greeny slicks off Nantucket. She had always thought of the sea as a healer. When she had worked in New York and winter had lingered, she had looked forward to the cold salt water of early summer to wash away her problems, both physical and mental. She supposed that the same efficacy, if there was one, was to be found in salt water wherever it was, but it did not feel the same. She had swum once in the English Channel and found the water cold and soupy, and the pebbles had hurt her feet. She wanted the seas she knew. Home.

But, whatever her yearnings, this was home now, this grey countryside, this rambling house set in the middle of what had once been England’s Great Forest, with its trees and shadows and dark, often impenetrable thickets. With Bill there she could ignore its gloom but now she was swept by homesickness, not only for the sea, but for California’s warmth and colour, for space, mountains, deserts, forests and great, cloudless skies.

There was a knock on the door and Miss Griffin came in. Rachel had met her for the first time on her return from hospital three days before, and did not care for her. Neither, she knew instinctively, did the woman like her. Bill had found her and told Rachel about her the first time he had come to see her in hospital after the accident, when she was still muzzy and shocked, scarcely aware of the conversation.

“We’re incredibly lucky,” he had said. “She’s a retired nurse who lives in Chichester. Not a thing of beauty and charm, but she seems efficient and likes babies. She wouldn’t commit herself, but I think she’ll stay as long as we need her.”

Later, Rachel realised he had not exaggerated their good fortune. Reliable children’s nurses were few and far between. They had been living in Lexton for such a short time that they had no friends who might have cared for Sophie. Bill’s parents were dead — as were her own — and he had no close relatives.

As she turned from the window the woman said, “I’ve put Sophie down. It’s nearly eleven, Mrs. Chater. Is there anything I can do for you?” Her tone was cold.

“Not a thing, thanks. I guess I’ll go and see Sophie as soon as I’m dressed.”

“I would suggest you left it for a while. I had trouble getting her to sleep.”

She turned and closed the door behind her with a snap. Rachel made a face at the rigid back.

As she dressed, she remembered how she had looked forward to her return, waiting in her private hospital room for Bill to collect her. For the first time, she had thought with affection of the gaunt, angular house he had bought before her arrival from America.

*

The first jolt to her happiness had occurred when the surgeon visited her. He was a sleek man running to plumpness and premature baldness. As befitted his membership of the private side of British medicine, he wore a dark jacket and striped trousers, a shirt of dark blue Bengal stripes and white collar; as a concession to youth, he wore a mauve silk tie.

He was pleasant enough, she thought, but his ponderous manner gave an impression of middle-age, though he could not have been more than thirty-six.

She was sitting on her bed when he arrived.

“Today’s the day,” he said. “How long have we had you now?”

“Three weeks.”

“A long time to be away from home, especially when you have a small baby.” As he talked he began to examine her knee.

“Does that hurt?”

“A little.”

“Can you bend it? Good. What’s her name?”

“Sophie.” He had asked her this twice before.

“I imagine your husband will be glad to see you back. Straighten it. A writer, isn’t he? Tell me, does he ... ? Can you lift it a little bit more? That’s better. Does he keep regular hours or does he write when the inspiration comes over him?”

It was one of a stock set of questions that people asked. “He goes to work every morning after breakfast, like anyone else. He has a room in the garden where he’s undisturbed.”

“Yes, well, that’s doing very nicely.” He closed her dressing-gown primly. “There’s always going to be a little stiffness. I think you must prepare yourself for that.”

They talked for a while about exercises and finally he said. “How do you feel about driving again?”

She was about to say she was terrified, but stopped herself. It was too emotional a word: a writer’s word. He might take her liter

ally, as he took most things, and so she said, “Apprehensive, I guess.”

“You won’t be able to do much for a while, anyway. The knee won’t stand the strain. Especially if you have to brake suddenly.”

“It won’t matter. My husband loves driving.”

“Your house is rather isolated, isn’t it?”

“I suppose so.”

“I’ve been out your way occasionally. Almost always get lost. Real Indian country.” He smiled at his little joke, then stood up.

“Good luck, Mrs. Chater.”

“Thank you.”

At the door, he turned. “It was sad about Leech,” he said. She looked up, startled. He had never mentioned Charlie before. “I knew him. His father was a jobbing gardener. He worked for my mother for years. In the school holidays he used to bring Charlie round from job to job. We played together as children.” He was staring at her. “The report of the inquest said he had been working for you.”

“Yes.”

“He was always good with his hands.”

Especially where his hands weren’t wanted, she thought bitterly. She did not want to discuss Charlie Leech, nor what had happened. But the doctor stood there while a little silence grew. Then he said, “It’s unfortunate your husband wasn’t home.”

When he had gone she found that her heart was beating rapidly. Why had he mentioned Charlie? What was he implying? Did he think that she and Charlie ... ? God, could he be thinking that she and Charlie had been having a squalid little affair while her husband was away? Is that what others would be thinking? Did Bill think that? She had rejected the idea as preposterous, but elements of it remained. It had not occurred to her before.

And then, as she waited for Bill, the dream suddenly became visible on her inner eye in chiaroscuro: first, the tapping ... She felt herself growing cold as she realised that she had dreamed the same dream at least three times. The tapping, the face and, most terrifying of all, the cat.

She told herself, as she had told herself since, that the events that had set off the dream were in the past. She remembered, from a course in classical history she had taken at Berkley, Polybius’s pragmatic view of history, and his thesis that what one learns from the past shapes one’s future behaviour. But there was nothing in the past, or at least, not in the past which inspired the dream, from which she could learn. The dream was simply a dream, reality coming to the surface of her mind in sleep, for everything about the dream had once been real, and she did not want to remember it. But it was not the past, but the future that was bothering her, and she knew at least one of the reasons: one day, when she was home she would have to see Mrs. Leech, Charlie’s widow. Bill had already visited her, given her money. Rachel had written saying how desperately sorry she was to have been the unwitting cause of his death. But she would have to see her. There was no escaping it.

Then Bill arrived and the joy of seeing him swept away the horrors. Temporarily.

At first she enjoyed the drive home. They passed a pub called the Fox and Grapes, where they had sometimes lunched, and a few minutes later turned off the main road and began to wind up into the folded, closed and secretive heart of the Downs, along a lane that ran between high thorn hedges. There were objects she recognised: a post-box, a red telephone kiosk standing isolated in the middle of nowhere, a flint farmhouse, hayricks that she had seen being built at the end of the previous summer, chicken houses, calf units, and everywhere trees. They passed into the parish of Lexton itself and all these things coalesced into her landscape of which, willy nilly, she was a part.

Lexton lay in a wooded valley surrounded by beechwood hangers which seemed to cut it off from the main stream of Sussex life. It had no centre in the sense of picturesque English postcard villages with their streams and ponds and rows of thatched cottages. It had a shop which combined its mercantile function with that of sub-post office; a pub; a harness-maker who now made wallets and belts as often as mending bridles and stirrup-leathers; a blacksmith who no longer shod horses but made ornamental iron-work; a book bindery and a bungalow advertising cream teas. But all were separated from each other by fields and copses; even the church stood alone.

When she had first arrived from America she had been reminded of the countryside between Paso Robles and the sea in central California. It was the same type of landscape, of rolling hills and winding roads, leading she never knew where, to cut-off places and secret valleys. But the difference here was the trees. She had never seen such woods. They rose out of the bottom land and towered up from the sides of the Downs, great hardwoods, beech and elm, ash and oak, magnificent umbrellas of green in summer, stark and witchlike in winter.

Once she had flown over the Downs in a helicopter with Bill.

“That’s where we live,” he had shouted, pointing. “There’s the house.” She had looked down and had hardly been able to detect the break in the trees which was their three acres of paddock and garden. Everywhere below seemed to be unbroken green.

It was only later, once she had begun, like a good immigrant, to read about her new land, that she found they were living in what remained of the Great Forest. A dark and frightening area which had stretched along the south coast of Britain in ancient times; a place of superstition and dread, harbouring only charcoal-burners, iron-workers and fugitives. It had once formed part of the Kingdom of the South Saxons, and in her reading she had come across names like Ella and Cissa, Aethelwald and Ceadwalla, who had lived and fought on the edge of the Great Forest. Sometimes, on a dull day, looking out of the drawing-room window across the paddock at the beech trees with their screaming rookeries, she was able to visualise the mile upon mile of gloomy forest, with only a pin-point of light to show where the iron-worker had his forge.

They came to a crossroads and Bill turned right. One lane looked very much like another and she was still not completely familiar with the sprawling parish which was said to have more than eighty miles of narrow, hedged roadway. Half-hidden by blackberries, she saw the sign which said Pickaxe Lane, and felt sick. This was the way she had driven Charlie home, this was where the accident had happened. They came to the crown of a rise. There was the tree she had hit. Momentarily her courage failed her and she looked down at her hands. Then she thought: don’t be so silly, it’s only a tree. As they drew level with it she looked for damage. She was not sure what to expect: a mass of torn foliage, smashed branches. But there was hardly anything to see: a single rip in the bark, a couple of sappy bruises where someone might have hit it with a large hammer; that was all. Then suddenly she was thrown forward as Bill braked.

“My Christ!” he said. “What’s that?”

She followed his glance. At first she could see nothing except a black boulder half-hidden by the tall grass. When the boulder moved she realised that it was an animal. It stood For a moment, watching them, then disappeared into the hedgerow.

“I’ve never seen a cat as big as that,” he said. “Never.”

Rachel knew it was the cat from her dream. The cat that had caused Charlie Leech’s death; the cat that had caused her to spend the past three weeks in hospital with a smashed knee. It was the cat.

She heard Bill say, with unusual vehemence: “I hate cats!”

Surprised, she turned to look at him. “Do you? I didn’t know that.”

He smiled at her. “You weren’t thinking of getting one, were you?”

“God, no! Not after what happened.”

For the rest of the drive she sat stiffly, saying nothing, seeing the great black shape in her mind’s eye, too absorbed in her thoughts to realise that Bill, too, was silent, looking ahead through the wind-shield, a frown drawing his eyebrows together.

A few minutes later the drive gates loomed up on the left and, behind them, the steeply-pitched roof of the house.

As he turned into the drive, she saw a notice on the gate. In big black letters drawn by a felt marker were the words, ‘Welcome home!’ She felt tears spring to her eyes and a lump form in her thr

oat and put her arm through his.

The house stood well back from the road at the end of a short, curving drive and was almost hidden by high beech hedges. It was tall and angular, like Bill himself, but instead of his easygoing charm it had, she thought, a gauntness and a secretiveness unlike most of the other soft, yellow-stoned cottages of Sussex. Parts of it dated from the sixteenth century and it had been added to over the years. In Victoria’s time it had been a rectory and another section, of grey flint had been built on. The constant additions had given it winding passages, two staircases, short corridors that seemed to lead nowhere. It was everything that Rachel’s childhood homes in California had not been. There she has been used to space and sunny colours, here small, damp, musty-smelling rooms opened into other small rooms that opened into passages that sometimes ended in blank walls. Her first reaction had been that she could never live in such a gloomy place but, just before her accident, when autumn had brought an early cold snap, she had begun to change her mind. The small rooms warmed by open fires or wood stoves, the wings which could be closed off, the huge farmhouse kitchen with its solid-fuel stove had, she realised, been designed for a way of life different from that of California, a cosy, indoor life insulated from the dismal prospect outside.

There were few trees near the house. They had been cut down years before and the three acres of grass gave the impression of being a clearing in the forest which, in fact, they were. At the back was a paddock overgrown by grass and nettles. Once it had been an orchard, but the trees had slowly died of neglect and canker and the last of them were waiting to be cut for firewood.

As Bill helped her out of the car the front door opened and a woman stood in the doorway. She was short and stocky. Her hair was iron-grey and basin-cut. She wore thick pebble glasses which exaggerated the size of her eyes and gave her a thyroid look. She was dressed in a flowered overall and had an air of severity and no-nonsense competence.

Thief Taker (A Macrae and Silver Mystery Book 3)

Thief Taker (A Macrae and Silver Mystery Book 3) Thief Taker

Thief Taker Threats and Menaces

Threats and Menaces Never Die in January

Never Die in January Venom

Venom Dirty Weekend (Macrae and Silver Book 1)

Dirty Weekend (Macrae and Silver Book 1) Cat's Eyes

Cat's Eyes Berlin Blind

Berlin Blind The Sea Cave

The Sea Cave Dirty Weekend

Dirty Weekend Burn Out (Dr. Anne Vernon Book 1)

Burn Out (Dr. Anne Vernon Book 1) Never Die in January (A Macrae and Silver Mystery Book 2)

Never Die in January (A Macrae and Silver Mystery Book 2)